The House in Prague Excerpt: Chapter 7 Leaving

Chapter 7: Leaving

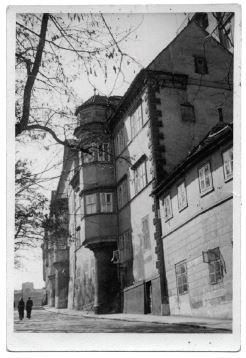

Loreta Square, No. 108, Prague

From The House in Prague: How a Stolen House Helped an Immigrant Girl Find Her Way Home

The Prague I am brought back to in the spring of 1939 seems like a different city. Nazi swastika flags everywhere, German uniforms in the streets. I am taken to the city’s center only twice ﹘ once to see a doctor, and once to shop for clothes because Mother needs me to try them on for size. The only people I see in the sidewalk cafes are German soldiers and officers. It is as if the people of Prague have vanished.

And now I don’t see Father at all, not even in the evenings. Instead, strangers sit down to supper with us ﹘ each night a different man. One evening the maid who is watching me decides we will walk down toward the river to observe the scene. We see many Germans in uniform. Strolling toward us comes a group of officers in black. As they advance, a street lamp lights up a silver skull mounted on one of the officers’ caps. Terrified, I scream when I see it. The maid rushes me back home.

When we return home, I discover that our upstairs rooms have been closed down. Bewildered, I run up the stairs and wander through the shuttered rooms. Where are my toys, my books? Everything seems in disarray. I am made to sleep in the big music room outside the door to my parents’ bedroom. It is a scary night.

In the morning, most of the paintings on the first floor of our home are removed. What does this mean? I run into the big hall outside the music room. There are huge trunks, propped open and half-full of dishes and art works, with newspapers crumpled between. Mother is filling other trunks with clothing. People keep bringing in more things to be packed. I see the maid with a pile of my clothing in her arms. There is my favorite light blue sweater with red heart-shaped buttons.

Our furniture is turned around, all out of place. Several pieces have stickers with numbers on them. Our paintings are on the floor in the hall, turned toward the wall, with the same stickers and numbers on them. Father’s secretary is busy writing numbers on a sheet of paper, making notes next to them. Some of my favorite paintings are missing entirely. Later I learn that Father has used several of them to ease the way for the permits and documents we needed to leave the country. No one has told me that we are leaving. After a while, I don’t need to be told.

ARE WE LEAVING?

I decide to approach Mother. I want my knowledge to be confirmed in spoken words.

“We’re leaving, aren’t we?” I ask.

Mother kneels down, wrapping her arms around me. “Yes, we are. Things aren’t safe here for us any longer, and we are going to America. But Anicko, you must keep this a secret or you’ll put us all in danger.” Seeing my frightened expression, she adds, “There will be a big World’s Fair going on in New York, and we are going to see it. Then we’ll come back home.”

“I don’t believe you!” I shout. “We are not coming back!”

I tear myself away, rushing out of the house and into the street. Turning left, I run on the cobbled sidewalk to the nearby Strahov monastery. Its beautiful fruit orchard is just beginning to bloom in the whites and rosy pinks of early spring. This is my friends’ and my favorite place to play. I look for some of them, and sure enough, I see Jana, Ruzenka, and my best friend, Marie, sitting on a bench. I wave and join them.

Marie is dressed just like me, in a sweater and pleated skirt. We are the same height, both of us with light brown braids. But while my eyes are green like Mother’s, hers are bright blue. If I had a sister, she would be like Marie.

My friends and I have invented a new game. One of us describes an imagined journey’s destination ﹘ a city or a country ﹘ without naming it. The others guess the name. When my turn comes, I say, “I am going to a country where the houses reach up to the sky and people shoot each other in the street.”

“America!” the three of them shout in unison. Marie notices my confused expression and guesses the truth.

“Anicko,” she says, “You really are going to America, aren’t you?” I flush with guilt, because I have betrayed the secret and endangered my family. I run away crying ﹘ and never see my friends again.

GOODBYES

The next day, the trunks in the hall are closed. Father returns home, saying we must leave quickly. For the last time, Father, Mother, my brothers, and I walk down the dark staircase that leads to the courtyard. I carry Suzanka, the doll Mother had brought me when she returned from a long concert tour. And I am wearing my new blue coat. Obeying a sudden impulse, I press my hand to the wall of the house and whisper goodbye.

Several people stand in the courtyard waiting to say good-bye ﹘ neighbors and people who worked for my parents. Embraces, whispers, tears. Father frowns with anxiety; Mother is pale and silent. I cling to Miss Cook, whose sweet-smelling kitchen has so often been my refuge.

Standing in the group is the nurse who took care of me whenever I was sick. She had taught me my prayers and helped me prepare for my First Communion. I see her take Mother’s handbag from her, open it, and stuff two holy pictures inside ﹘ one of the Sacred Heart, the other of St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers.

“They will protect you,” she tells Mother. Mother smiles, hugs her, and says nothing. Then it is time. Father takes my hand, Mother turns back for one last look at the house. The five of us walk out into the street where our car and driver are waiting. We drive silently down the hill toward the city’s center.

GRANDMOTHER

Our first stop is the home of my grandmother, an apartment near the river. In spite of Father’s pleading, she will not come with us. So we must go to say good-bye. We park and climb the stairs, none of us saying a word. I pinch myself hard so I won’t cry. She opens her door and we walk into the familiar apartment that is filled with mementos and pictures of us, our aunts, uncles, cousins, and our dead grandfather.

There are also pictures of her in-laws, our great-grandparents, who spent their lives among the few Jews in Kácov. Now my brothers and I wait in Grandmother’s living room, as she and my parents talk.

They stand close together: Father, tall and formal in a dark three-piece suit, with his tie and the gold glint of his watch chain adding the only bit of color; Mother, slight and beautiful in a violet outfit with fur around her throat; and Grandmother, in her customary dark dress that reaches to the floor. I stand frozen, watching them.

Then Grandmother moves toward us, the children. She speaks with my brothers first. I can’t hear what she says to them, but her expression is so serious and at the same time so loving. Karel, the oldest of us, embraces her with tears in his eyes. Pavel buries his face in her shoulder.

At last she comes to me. She puts her arms around me, holds me close, and this time I can’t stop the tears. I smell her familiar musky cologne. She murmurs some words that I can’t understand and kisses me. As we make our way down the stairs, I turn back and see her watching from her landing. I hear her long sigh as we walk out to the street.

View of the House from the Uvoz